Figure 1: The 3-tier Architecture of Linux Virtual Server

This paper describes the motivation, design, internal implementation of Linux Virtual Servers. The goal of Linux Virtual Servers is to provide a basic framework to build highly scalable and highly available network services using a large cluster of commodity servers. The TCP/IP stack of Linux kernel is extended to support three IP load balancing techniques, which can make parallel services of different kinds of server clusters to appear as a service on a single IP address. Scalability is achieved by transparently adding or removing a node in the cluster, and high availability is provided by detecting node or daemon failures and reconfiguring the system appropriately.

With the explosive growth of the Internet, Internet servers must cope with greater demands than ever. The potential number of clients that a server must support has dramatically increased, some hot sites have already received hundreds of thousands of simultaneous client connections. With the increasing number of users and the increasing workload, companies often worry about how the system grow over time. Furthermore, rapid response and 24x7 availability are mandatory requirements for the mission-critical business applications, as sites compete for offering users the best access experience. Therefore, the requirements for hardware and software solution to support highly scalable and highly available services can be summarized as follows:

A single server is usually not sufficient to handle this aggressively increasing load. The server upgrading process is complex, and the server is a single point of failure. The higher end the server is upgraded to, the much higher cost we have to pay.

Clusters of servers, connected by a fast network, are emerging as a viable architecture for building highly scalable and highly available services. This type of loosely coupled architecture is more scalable, more cost-effective and more reliable than a tightly coupled multiprocessor system. However, a number of challenges must be addressed to make a cluster of servers function effectively for scalable network services.

Linux Virtual Server (lvs) is a solution to the requirements. Linux Virtual Server directs network connections to the different servers according to scheduling algorithms and makes parallel services of the cluster to appear as a virtual service on a single IP address. Client applications interact with the cluster as if it were a single server. The clients are not affected by interaction with the cluster and do not need modification. Scalability is achieved by transparently adding or removing a node in the cluster. High availability is provided by detecting node or daemon failures and reconfiguring the system appropriately.

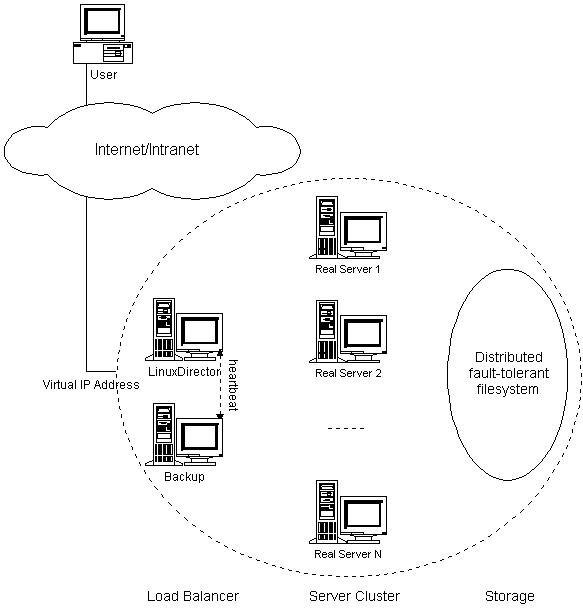

In this section we present a system architecture for building highly scalable and highly available network services on clusters. The three-tier architecture of LVS illustrated in Figure 1 includes:

Figure 1: The 3-tier Architecture of Linux Virtual Server

The load balancer handles incoming connections using IP load balancing techniques, it selects servers from the server pool, maintains the state of concurrent connections and forwards packets, and all the work is performed inside the kernel, so that the handling overhead of the load balancer is low. Therefore, the load balancer can handle much larger number of connections than a general server, thus a load balancer can schedule a large number of servers and it will not be a bottleneck of the whole system soon.

The server nodes in the above architecture may be replicated for either scalability or high availablity. Scalability is achieved by transparently adding or removing a node in the cluster. When the load to the system saturates the capacity of existing server nodes, more server nodes can be added to handle the increasing workload. Since the dependence of most network services is often not high, the aggregate performance should scale linearly with the number of nodes in the system, before the load balancer becomes a new bottleneck of the system. Since the commodity servers are used as building blocks, the performance/cost ratio of the whole systemis as high as that of commodity servers.

One of the advantages of a clustered system is that it has hardware and software redundancy. High availability can be provided by detecting node or daemon failures and reconfiguring the system appropriately so that the workload can be taken over by the remaining nodes in the cluster. We usually have cluster monitor daemons running on the load balancer to monitor the health of server nodes, if a server node cannot be reached by ICMP ping or there is no response of the service in the specified period, the monitor will remove or disable the server in the scheduling table of the load balancer, so that the load balancer will not schedule new connections to the failed one and the failure of server nodes can be masked.

Now, the load balancer may become a single failure point of the whole system. In order to prevent the failure of the load balancer, we need setup a backup of the load balancer. Two heartbeat daemons run on the primary and the backup, they heartbeat the health message through heartbeat channels such as serial line and UDP periodically. When the heartbeat daemon on the backup cannot hear the health message from the primary in the specified time, it will use ARP spoofing (gratutious ARP) to take over the virtual IP address to provide the load-balancing service. When the primary recovers from its failure, there are two methods. One is that the primary becomes to the backup of the functioning load balancer; the other is that the daemon receives the health message from the primary and releases the virtual IP address, and the primary will take over the virtual IP address. However, the failover or the takeover of the primary will cause the established connection in the state table lost in the current implementation, which will require the clients to send their requests again.

The backend storage is usually provided by is distributed fault-tolerant file systems, such as GFS, Coda, or Intermezzo. These systems also take care of availability and scalability issue of file system accesses. The server nodes access the distributed file system like a local file system. However, multiple identical applications running on different server nodes may access a shared resource concurrently, any conflitcing action by the applications must be reconciled so that the resource remains in a consistent state. Thus, there needs a distributed lock manager (internal of the distributed file system or external) so that application developers can easily program to coordinate concurrent access of applications running on different nodes.

Since the IP load balancing techniques have good scalability, Linux Virtual Server extend the TCP/IP stack of the Linux kernel to support three IP load balancing techniques, LVS/NAT, LVS/TUN and LVS/DR. The box running Linux Virtual Server act as a load balancer of network connections from clients who know a single IP address for a service, to a set of servers that actually perform the work. In general, real servers are idential, they run the same service and they have the same set of contents. The contents are either replicated on each server's local disk, shared on a network file system, or served by a distributed file system. We call data communication between a client's socket and a server's socket {\bf connection}, no matter it talks TCP or UDP protocol. The following subsections describe the working principles of three techniques and their advantages and disadvantages.

Due to the shortage of IP address in IPv4 and some security reasons,

more and more networks use private IP addresses which cannot be used

on the Internet. The need for network address translation arises when

hosts in internal networks want to access or to be accessed on the

Internet. Network address translation relies on the fact that the

headers of packets can be adjusted appropriately so that clients

believe they are contacting one IP address, but servers at different

IP addresses believe they are contacted directly by the clients. This

feature can be used to build a virtual server, i.e. parallel services

at the different IP addresses can appear as a virtual service on a

single IP address.

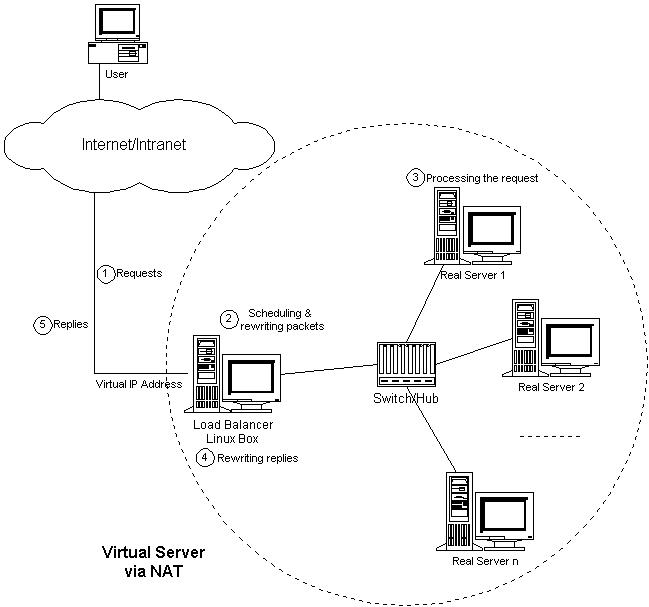

Figure 2: Architecture of LVS/NAT

The architecture of Linux Virtual Server via NAT is illustrated in Figure 2. The load balancer and real servers are interconnected by a switch or a hub. The workflow of LVS/NAT is as follows: When a user accesses a virtual service provided by the server cluster, a request packet destined for virtual IP address (the IP address to accept requests for virtual service) arrives at the load balancer. The load balancer examines the packet's destination address and port number, if they are matched for a virtual service according to the virtual server rule table, a real server is selected from the cluster by a scheduling algorithm, and the connection is added into the hash table which records connections. Then, the destination address and the port of the packet are rewritten to those of the selected server, and the packet is forwarded to the server. When an incoming packet belongs to an established connection, the connection can be found in the hash table and the packet will be rewritten and forwarded to the right server. When response packets come back, the load balancer rewrites the source address and port of the packets to those of the virtual service. When a connection terminates or timeouts, the connection record will be removed in the hash table.

IP tunneling (IP encapsulation) is a technique to encapsulate IP

datagram within IP datagram, which allows datagrams destined for one

IP address to be wrapped and redirected to another IP address. This

technique can be used to build a virtual server that the load balancer

tunnels the request packets to the different servers, and the servers

process the requests and return the results to the clients directly,

thus the service can still appear as a virtual service on a single IP

address.

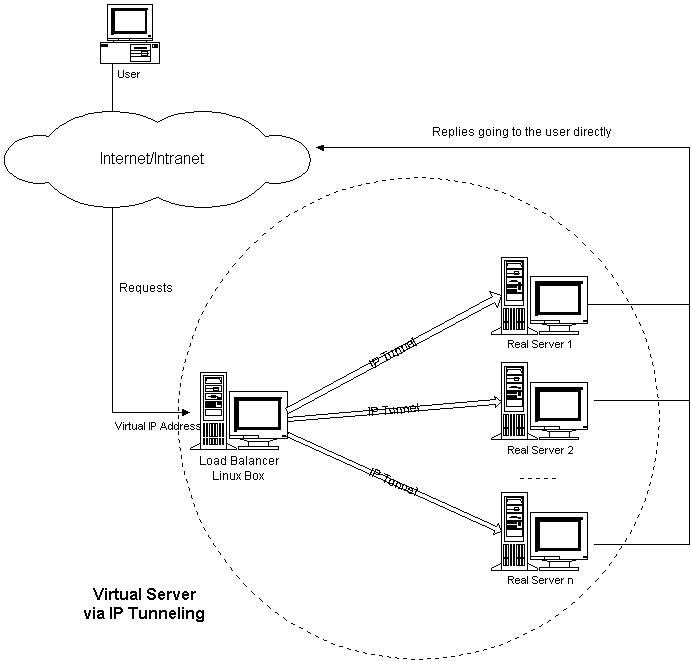

Figure 3: Architecture of LVS/TUN

The architecture of Linux Virtual Server via IP tunneling is illustrated in Figure 3. The real servers can have any real IP address in any network, and they can be geographically distributed, but they must support IP tunneling protocol and they all have one of their tunnel devices configured with VIP.

The workflow of LVS/TUN is the same as that of LVS/NAT. In LVS/TUN, the load balancer encapsulates the packet within an IP datagram and forwards it to a dynamically selected server. When the server receives the encapsulated packet, it decapsulates the packet and finds the inside packet is destined for VIP that is on its tunnel device, so it processes the request, and returns the result to the user directly.

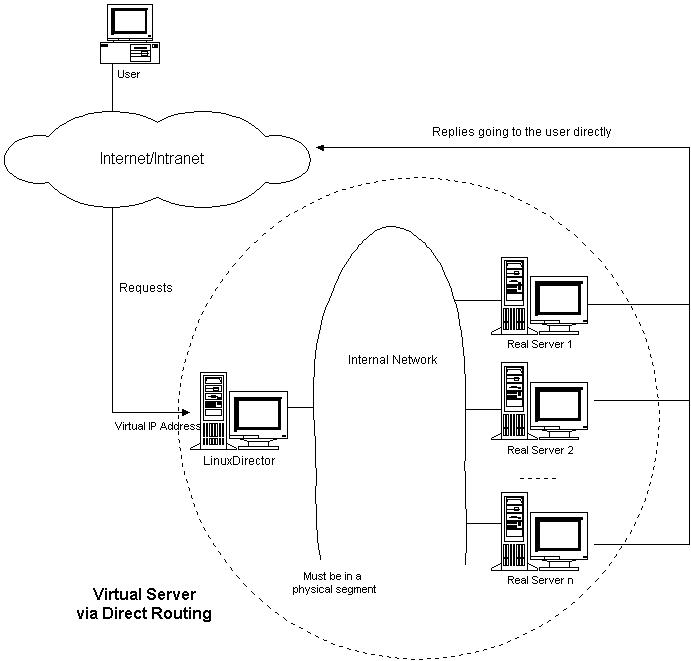

This IP load balancing approach is similar to the one implemented in

IBM's NetDispatcher. The architecture of LVS/DR is illustrated in

Figure 4. The load balancer and the real servers must have one of

their interfaces physically linked by an uninterrupted segment of LAN

such as a HUB/Switch. The virtual IP address is shared by real

servers and the load balancer. All real servers have their loopback

alias interface configured with the virtual IP address, and the load

balancer has an interface configured with the virtual IP address to

accept incoming packets.

Figure 4: Architecture of LVS/DR

The workflow of LVS/DR is the same as that of LVS/NAT or LVS/TUN. In LVS/DR, the load balancer directly routes a packet to the selected server, i.e. the load balancer simply changes the MAC address of data frame to that of the server and retransmits it on the LAN. When the server receives the forwarded packet, the server finds that the packet is for the address on its loopback alias interface and processes the request, finally returns the result directly to the user. Note that real servers' interfaces that are configured with virtual IP address should not do ARP response, otherwise there would be a collision if the interface to accept incoming traffic for VIP and the interfaces of real servers are in the same network.

| LVS/NAT | LVS/TUN | LVS/DR | |

| Server | any | tunneling | non-arp dev |

| server network | private | LAN/WAN | LAN |

| server number | low (10\~20) | high (100) | high (100) |

| server gateway | load balancer | own router | own router |

Table 1: The comparison of LVS/NAT, LVS/TUN and LVS/DR

The characteristics of three IP load balancing techniques are summarized in Table 1.

In LVS/NAT, real servers can run any operating system that supports TCP/IP protocol, and only one IP address is needed for the load balancer and private IP addresses can be used for real servers.

The disadvantage is that the scalability of LVS/NAT is limited. The load balancer may be a bottleneck of the whole system when the number of server nodes increase to around 20 which depends on the throughout of servers, because both request and response packets need to be rewritten by the load balancer. Supposing the average length of TCP packets is 536 Bytes and the average delay of rewriting a packet is around 60us on the Pentium processor (this can be reduced a little by using of faster processor), the maximum throughout of the load balancer is 8.93 Mbytes/s. The load balancer can schedule 15 servers if the average throughout of real servers is 600KBytes/s.

For most Internet services (such as web service) that request packets are often short and response packets usually carry large amount of data, a LVS/TUN load balancer may schedule over 100 general real servers and it won't be the bottleneck of the system, because the load balancer just directs requests to the servers and the servers reply the clients directly. Therefore, LVS/TUN has good scalability. LVS/TUN can be used to build a virtual server that takes huge load, extremely good to build a virtual proxy server because when the proxy servers receive requests, they can access the Internet directly to fetch objects and return them to the clients directly.

However, LVS/TUN requires servers support IP Tunneling protocol. This feature has been tested with servers running Linux. Since the IP tunneling protocol is becoming a standard of all operating systems, LVS/TUN should be applicable to servers running other operating systems.

Like LVS/TUN, a LVS/DR load balancer processes only the client-to-server half of a connection, and the response packets can follow separate network routes to the clients. This can greatly increase the scalability of virtual server.

Compared to LVS/TUN, LVS/DR doesn't have tunneling overhead , but it requires the server OS has loopback alias interface that doesn't do ARP response, the load balancer and each server must be directly connected to one another by a single uninterrupted segment of a local-area network.

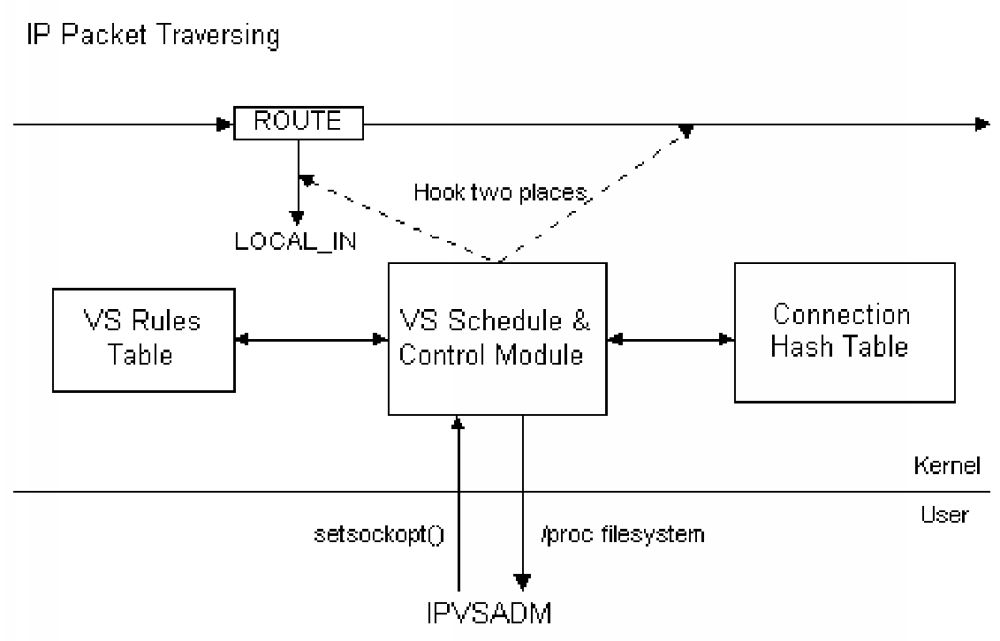

We have modified the TCP/IP stack inside Linux kernel 2.0 and 2.2

respectively, in order to support the above three IP load balancing

technologies. The system implementation of LinuxDirector is

illustrated in Figure 5. The ``VS Schedule \& Control Module'' is the

main module of LinuxDirector, it hooks two places at IP packet

traversing inside kernel in order to grab/rewrite IP packets to

support IP load balancing. It looks up the ``VS Rules'' hash table for

new connections, and checks the ``Connection Hash Table'' for

established connections. The ``IPVSADM'' user-space program is to

administrator virtual servers, it uses setsockopt function to modify

the virtual server rules inside the kernel, and read the virtual

server rules through /proc file system.

Figure 5: Implimentation of LinuxDirector

The connection hash table is designed to hold millions of concurrent

connections, and each connection entry only occupies 128 bytes

effective memory in the load balancer. For example, a load balancer of

256 Mbytes free memory can have two million concurrent

connections. The hash table size can be adapted by users according to

their applications, and the client \(

LinuxDirector implements ICMP handling for virtual services. The

incoming ICMP packets for virtual services will be forwarded to the

right real servers, and outgoing ICMP packets from virtual services

will be altered and sent out correctly. This is important for error

and control notification between clients and servers, such as the MTU

discovery.

LinuxDirector implements three IP load balancing techniques. They can

be used for different kinds of server clusters, and they can also be

used together in a single cluster, for example, packets are forwarded

to some servers through VS/NAT method, some servers through VS/DR, and

some geographically distributed servers through VS/TUN.

We have implemented four scheduling algorithms for selecting servers

from the cluster for new connections: Round-Robin, Weighted

Round-Robin, Least-Connection and Weighted Least-Connection. The first

two algorithms are self-explanatory, because they don't have any load

information about the servers. The last two algorithms count active

connection number for each server and estimate their load based on

those connection numbers.

Round-robin scheduling algorithm directs the network connections to

the different servers in the round-robin manner. It treats all real

servers as equals regardless of number of connections or response

time. Although the round-robin DNS works in this way, there are quite

different. The round-robin DNS resolves the single domain to the

different IP addresses, the scheduling granularity is per host, and

the caching of DNS hinder the algorithm take effect, which will lead

to significant dynamic load imbalance among the real servers. The

scheduling granularity of virtual server is per connection, and it is

more superior to the round-robin DNS due to fine scheduling

granularity.

The weighted round-robin scheduling can treat the real servers of

different processing capacities. Each server can be assigned a weight,

an integer that indicates its processing capacity, the default weight

is 1. The WRR scheduling works as follows:

Assuming that there is a list of real servers (S={S_{0}, S_{1}, ...,

S_{n-1}}), an index (i) is the last selected server in (S), the

variable (cw) is current weight. The variables (i) and (cw) are

first initialized to zero. If all (W(S_{i})=0), there are no

available servers, all the connection for virtual server are dropped.

while (1) {

if (cw <= 0) {

} else i = (i + 1) mod n;

if (W(Si) >= cw) return Si;

In the WRR scheduling, all servers with higher weights receives new

connections first and get more connections than servers with lower

weights, servers with equal weights get an eaqual distribution of new

connections. For example, the real servers A,B,C have the weights

4,3,2 respectively, then the scheduling sequence can be AABABCABC in a

scheduling period (mod sum(Wi)). The WRR is efficient to schedule

request, but it may still lead to dynamic load imbalance among the

real servers if the load of requests vary highly.

The least-connection scheduling algorithm directs network connections

to the server with the least number of active connections. This is one

of dynamic scheduling algorithms, because it needs to count active

connections for each server dynamically. At a virtual server where

there is a collection of servers with similar performance, the

least-connection scheduling is good to smooth distribution when the

load of requests vary a lot, because all long requests will not be

directed to a single server.

At a first look, the least-connection scheduling can also perform well

even if servers are of various processing capacities, because the

faster server will get more network connections. In fact, it cannot

perform very well because of the TCP's TIME\_WAIT state. The TCP's

TIME\_WAIT is usually 2 minutes, in which a busy web site often get

thousands of connections. For example, the server A is twice as

powerful as the server B, the server A has processed thousands of

requests and kept them in the TCP's TIME\_WAIT state, but but the

server B is slow to get its thousands of connections finished and

still receives new connections. Thus, the least-connection scheduling

cannot get load well balanced among servers with various processing

capacities.

The weighted least-connection scheduling is a superset of the

least-connection scheduling, in which a performance weight can be

assigned to each server. The servers with a higher weight value will

receive a larger percentage of active connections at any time. The

virtual server administrator can assign a weight to each real server,

and network connections are scheduled to each server in which the

percentage of the current number of active connections for each server

is a ratio to its weight.

The weighted least-connections scheduling works as follows: supposing

there is n real servers, each server i has weight (W_{i}) (i=1,..,n)

and active connections (C_{i}) (i=1,..,n), all connection number S

is the sum of (C_{i}) (i=1,..,n), the network connection will be

directed to the server j, in which

Since the S is a constant in this lookup, there is no need to divide

(C_{i}) by S, it can be optimized as

Since there is no floats in Linux kernel mode, the comparison of

(C_{j}/W_{j} > C_{i}/W_{i}) is changed to (C_{j}*W_{i} >

C_{i}*W_{j}) because all weights are larger than zero.

Up to now, we have assumed that each network connection is independent

of every other connection, so that each connection can be assigned to

a server independently of any past, present or future assignments.

However, there are times that two connections from the same client

must be assigned to the same server either for functional or for

performance reasons.

FTP is an example for a functional requirement for connection

affinity. The client establishs two connections to the server, one is

a control connection (port 21) to exchange command information, the

other is a data connection (usually port 20) to transfer bulk data.

For active FTP, the client informs the server the port that it listens

to, the data connection is initiated by the server from the server's

port 20 to the client's port. Linux Virtual Server could examine the

packet coming from clients for the port that client listens to, and

create any entry in the hash table for the coming data connection.

But for passive FTP, the server tells the clients the port that it

listens to, the client initiates the data connection to that port of

the server. For the LVS/TUN and the LVS/DR, Linux Virtual Server is

only on the client-to-server half connection, so it is imposssible for

Linux Virtual Server to get the port from the packet that goes to the

client directly.

SSL (Secure Socket Layer) is an example of a protocol that has

connection affinity between a client and a server for performance

reasons. When a SSL connection is made, port 443 for secure Web

servers and port 465 for secure mail server, a key for the connection

must be chosen and exchanged. Since it is time-consuming to negociate

and generate the SSL key, the successive connections from the same

client can also be granted by the server in the life span of the SSL

key.

Our current solution to client affinity is to add persistent port

handling. When a client first accesses the service marked persistent,

the load balancer will create a connection template between the given

client and the selected server, then create an entry for the

connection in the hash table. The template expires in a configurable

time, and the template won't expire if it has its controlled

connections. Before the template expires, the connections for any port

from the client will send to the right server according to the

template. Although the persistent port may cause slight load

imbalance among servers because its scheduling granularity is per

host, it is a good solution to connection affinity.

Cluster management is a serious concern for LVS systems of many

nodes. First, the cluster management should make it easier for system

administrators to setup and manage the clusters, such as adding more

machines earlier to improve the throughput and replacing them when

they break. Second, the management software can provide

self-configuration with respect to different load distribution and

self-heal with node/service failure and recovery. See other white

papers for how piranha manages the cluster.

In the client/server applications, one end is the client, the other

end is the server, and there may be a proxy in the middle. Based on

this scenario, we can see that there are many ways to dispatch

requests to a cluster of servers in the different levels. Existing

request dispatching techniques can be classified into the following

categories:

Berkeley's Smart Client (smartc) suggests that the service

provide an applet running at the client side. The applet makes

requests to the cluster of servers to collect load information of all

the servers, then chooses a server based on that information and

forwards requests to that server. The applet tries other servers when

it finds the chosen server is down. However, these client-side

approaches are not client-transparent, they requires modification of

client applications, so they cannot be applied to all TCP/IP

services. Moreover, they will potentially increase network traffic by

extra querying or probing.

The NCSA scalable web server is the first prototype of a scalable web

server using the Round-Robin DNS approach (ncsa1, ncsa2, rrdns).

The RRDNS server maps a single name to the different IP addresses in a

round-robin manner so that the different clients will access the

different servers in the cluster for the ideal situation and load is

distributed among the servers. However, due to the caching nature of

clients and hierarchical DNS system, it easily leads to dynamic load

imbalance among the servers, thus it is not easy for a server to

handle its peak load. The TTL(Time To Live) value of a name mapping

cannot be well chosen at RR-DNS, with small values the RR-DNS will be

a bottleneck, and with high values the dynamic load imbalance will get

even worse. Even the TTL value is set with zero, the scheduling

granularity is per host, different client access pattern may lead to

dynamic load imbalance, because some clients (such as a proxy server)

may pull lots of pages from the site, and others may just surf a few

pages and leave. Futhermore, it is not so reliable, when a server

node fails, the clients who maps the name to the IP address will find

the server is down, and the problem still exists even if they press

"reload" or "refresh" button in the browsers.

EDDIE, Reverse-proxy, and SWEB

use the application-level scheduling approach to build a scalable web

server. They all forward HTTP requests to different web servers in the

cluster, then get the results, and finally return them to the clients.

However, this approach requires to establish two TCP connections for

each request, one is between the client and the load balancer, the

other is between the load balancer and the server, the delay is

high. The overhead of dealing HTTP requests and replies in the

application-level is high. Thus the application-level load balancer

will be a new bottleneck soon when the number of server nodes

increases.

Berkeley's MagicRouter and Cisco's

LocalDirector use the Network Address Translation

approach similar to the NAT approach used in Linux Virtual

Server. However, the MagicRouter doesn't survive to be a useful system

for others, the LocalDirector is too expensive, and they only support

part of TCP protocol.

IBM's TCP router uses the modified Network Address

Translation approach to build scalable web server on IBM scalable

Parallel SP-2 system. The TCP router changes the destination address

of the request packets and forwards the chosen server, that server is

modified to put the TCP router address instead of its own address as

the source address in the reply packets. The advantage of the modified

approach is that the TCP router avoids rewriting of the reply packets,

the disadvantage is that it requires modification of the kernel code

of every server in the cluster. NetDispatcher (netd) , the

successor of TCP router, directly forwards packets to servers that is

configured with router address on non arp-exported interfaces. The

approach, similar to the LVS/DR in Linux Virtual Server, has good

scalability, but NetDispatcher is a very expensive commercial product.

ONE-IP requires that all servers have their own IP

addresses in a network and they are all configured with the same

router address on the IP alias interfaces. Two dispatching techniques

are used, one is based on a central dispatcher routing IP packets to

different servers, the other is based on packet broadcasting and local

filtering. The advantage is that the rewriting of response packets can

be avoided. The disadvantage is that it cannot be applied to all

operating systems because some operating systems will shutdown the

network interface when detecting IP address collision, and the local

filtering also requires modification of the kernel code of server.

Linux Virtual Server extends the TCP/IP stack of Linux kernel to

support three IP load balancing techniques, LVS/NAT, LVS/TUN and

LVS/DR. Currently, four scheduling algorithms have been developed to

meet different application situations. Scalability is achieved by

transparently adding or removing a node in the cluster. High

availability is provided by detecting node or daemon failures and

reconfiguring the system appropriately. The solutions require no

modification to either the clients or the servers, and they support

most of TCP and UDP services. Linux Virtual Server is designed for

handling millions of concurrent connections.

We would like to thank Julian Anastasov for his bug fixes, suggestions

and smart comments to the LVS code. Thanks must go to many other

contributors to the Linux Virtual Server project too.

Connection Scheduling

Round-Robin Scheduling

Weighted Round-Robin Scheduling

if (i == 0) {

cw = cw - 1;

set cw the maximum weight of S;

if (cw == 0) return NULL;

}

}

Least-Connection Scheduling

Weighted Least-Connection Scheduling

Connection Affinity

Cluster Management

Alternative Approaches

Conclusions

Acknowledgements